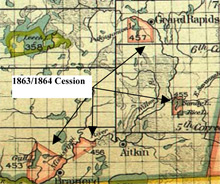

1863 & 1864: Land Cession Treaties with the Ojibwe (Mississippi, Pillager, Lake Winnibigoshish Bands)

Chippewa of the Mississippi, Pillager and the Lake Winnibigoshish Bands signed March 11, 1863 and May 7, 1864 in Washington, D. C.

During the Dakota War of 1862, there was some dissension among the Ojibwe on which side to support: the Dakota, or the U.S. The Mille Lacs band unequivocally sided with the U.S., actively protecting white settlers and military installations. As a result, in their treaty with the U.S. in 1863, the Mille Lacs band became “unmovable,” securing their reservation against future legal maneuverings.

The Ojibwe representatives in Washington, however, did cede several other reservations, in exchange for the extension of annuity payments from earlier treaties, and funding for farming and milling. In addition, prominent Ojibwe individuals received $16,000 in cash and two-story houses.

The direct payments to individuals who signed the 1863 treaty were one aspect of a larger U.S. role in internal Ojibwe politics and life ways. The treaty also defined for the time in U.S. terms what an Ojibwe “chief” would be: a leader of a band of at least 50 people, who would encourage “the pursuits of civilized life,” A “board of visitors” representing Christian religious denominations would report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs on the “qualifications and deportment of all persons residing upon the reservation.”

The U.S. unilaterally made several changes to this treaty before it was ratified by the Senate. The following year, Hole in the Day (who did not attend the 1863 treaty) led another delegation to Washington to secure a revised treaty. As a result, the boundaries of the reservation retained by the Ojibwe were changed. Also, the payment to prominent individuals as a group was reduced and a $5,000 payment to Hole in the Day was added; Hole in the Day and two other leaders received sections of land. The board of visitors was given the authority to name the date and manner of annuity payments, and to withhold payments from any “person of full or mixed blood, educated or partially educated, whose fitness, morally or otherwise, is not conducive to the welfare of said Indians.”