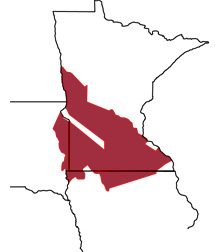

1851 Dakota Land Cession Treaties

Treaty with the Sioux, Signed July 23, 1851 at Traverse des Sioux, MN

Treaty with the Sioux, Signed August 6, 1851 at Mendota

In these transformative treaties, Dakota people sold most of their land to the U.S. in exchange for $3,750,000 (estimated at 12 cents per acre), to be paid over decades. Little of the payment was received. The treaty stipulated that they would retain a strip of land 20 miles wide, spanning the Minnesota River; this article was unilaterally removed by the U.S. Senate, but later reinstated by legislation.

In their report to Congress on these treaties, commissioners Alexander Ramsey and Luke Lea justified this enormous land cession by the Dakota – “larger than the State of New York, and rich, fertile, and beautiful, beyond description” – by writing that…

"It is needed as an additional outlet to the overwhelming tide of migration which is both increasing and irresistible in its westward progress."

At least two things are misleading about this statement.

First, there was no tide of migration to Dakota country in 1851. In the 1850 census, the entire “white and mulatto” population of Minnesota Territory (which stretched far into present-day North and South Dakota) was less than 6,100 people, living on more than 9,000 square miles ceded by Dakota and Ojibwe people in 1837 and 1847. (By contrast, Lea and Ramsey estimated that 8,000 Dakota people would be affected by these treaties.) The U.S. acquisition of another 35,000 square miles was “necessitated” not by settlers anxious to move there – although the land was, of course, very attractive – but by land speculators who wanted to divert migration to Minnesota from Iowa and Wisconsin, which had recently become states. The land cession did result in a “tide of migration,” but was not directly caused by one.

Secondly, Ramsey and Lea did not mention the interests of fur traders in the treaty, though they were well aware that traders had engineered the entire land cession. As Lucille Kane noted in “The Sioux Treaties and the Traders,”

"… by 1851 the traders had on their books debts amounting to almost half a million dollars. The fur trade was declining, and, without other means of getting their money, the traders looked to the funds the Indians would receive for their lands after signing the treaties. When the call for the treaty went out, traders flocked from posts near and far to Traverse des Sioux and Mendota to push the negotiations."—Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1851, p. 281

Of the compensation promised to the Dakota for their land, debt payments – inflated by the traders – came off the top. Another $60,000 was to be spent hiring (white) blacksmiths and preparing the Dakota to make a transition to farming. The remainder was to be placed in trust, with 5% paid to the Dakota per year. Of this money, half would be used to buy goods and services from the traders.

Though the benefits to traders and speculators are entirely omitted in their report, Ramsey and Lea spent pages talking about how the Dakota would benefit from the reduction of their homeland to a strip only 20 miles wide. The greatest benefit, in the eyes of Ramsey and Lea, would be an assault on Dakota culture:

"It was our constant aim to do what we could to break up the community system among the Indians, and cause them to recognise the individuality of property… If timely measures are taken for the proper location and management of these tribes, they may, at no distant period, become an intelligent and Christian people."