In their treaties with the United States, some Ojibwe bands retained the right to hunt, fish, and gather wild rice on ceded lands. In the 20th century, Ojibwe who tried to exercise their treaty-guaranteed harvesting rights were fined or arrested because they did not abide by state game laws. Inspired by tribes in the northwest, Wisconsin, and Michigan, the Ojibwe successfully defended their treaty-guaranteed fishing rights through the federal courts.

“For centuries the Chippewa have hunted, fished, and gathered wild foods. These activities . . . remain in a very real sense central to the culture and identity of the Chippewa.“

— Mark D. Slonim, attorney for Mille Lacs, during oral arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court (Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians), 1998

U.S. Forest Service Officer Wilbur Isaacson examines a wild rice season notice posted at Waboose Bay in 1958. For most of the 20th century, tribal members were subject to restrictions on their harvesting of traditional resources, particularly within state and federal lands. | Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, Great Lakes Region, Chicago

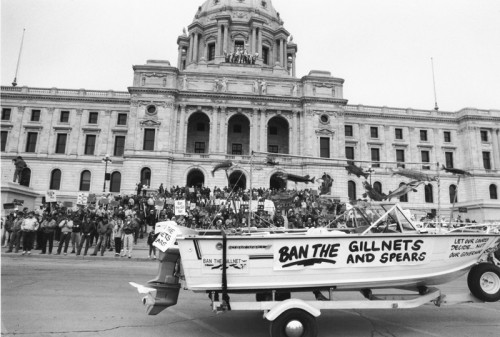

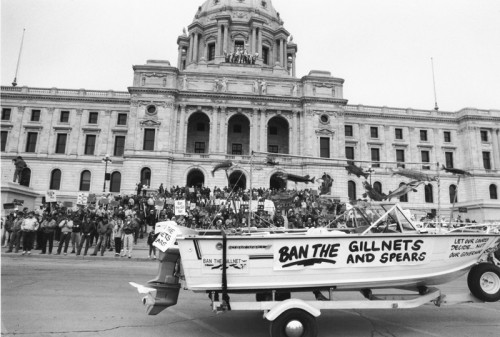

Backlash

Tribal efforts to practice treaty-guaranteed rights provoked a strong reaction from some Minnesotans who opposed Indian rights to fish off the reservation and out of season. Opponents complained that traditional spear fishing and netting practices would decimate fish populations and destroy tourism. The groups demanded that tribal people adhere to state game regulations, and denounced what their members considered special rights for Indians.

Holding banners and chanting slogans, protestors held rallies at the Minnesota State Capitol to denounce tribal fishing practices. | Photo by Joe Allan, courtesy of the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission

Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians

In 1990, the Mille Lacs Band sued the state of Minnesota, asserting that an 1837 treaty gave them the right to hunt, fish, and gather free of state regulation on former tribal lands.

To prevent a lengthy lawsuit, the state natural resources department and the Mille Lacs Band proposed a compromise. When the Minnesota legislature rejected the proposal, the Mille Lacs Band proceeded with their lawsuit, which went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1999, the court upheld Ojibwe treaty rights to harvest natural resources on lands ceded through treaty to the United States.

A walleye netted on Lake Mille Lacs in 2009. | Photo by Sue Erickson, courtesy of the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission

Some Ojibwe, such as these men at Mille Lacs Lake in 1998, use motorboats and headlamps to sustain tribal spear fishing traditions and defend treaty-guaranteed fishing rights. | Photo by Charles Rasmussen, courtesy of the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission