In negotiations with Native nations, American officials promised that Indian reservations would always belong to the tribes, and that treaty payments and provisions would be delivered in full and on time. Dakota and Ojibwe people were promised everlasting possession of their reservation lands. However, time would show that these promises were not to be honored.

Angered by a string of broken treaty promises and the loss of their territories, Dakota warriors and members of a sovereign nation chose to defend their lifeways in battle in 1862. Five weeks later, the war was over, and Dakota people faced revenge, punishment, and exile for their actions. In response, the United States nullified all of their treaties, sold their tribal lands, and redirected treaty payments to settlers who clamored for war reparations.

Five years later in 1867, the U.S. negotiated a new treaty that would relocate all Ojibwe people in Minnesota to a new reservation: White Earth. Many Ojibwe resisted the removal effort and, like the Dakota, chose to assert their sovereignty and defend their treaty-guaranteed rights to retain their original reservation lands.

Over the intervening decades, the U.S. exploited tribal resources and attempted to dismantle tribal land ownership by dividing reservations into parcels for allotment to individual tribal members.

The Dakota React to Broken Treaties

Dakota people believed the government would live up to its agreements that treaty payments and provisions would be delivered in full and on time. Instead, broken treaties resulted in hunger, distress, and desperation.

If I were to give you an account of all the money that . . . you sent but which never reached us, it would take all night to tell it.

— Dakota Chief Little Crow to Charles E. Mix, U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1858

Protecting Loved Ones: The Dakota War of 1862

In 1862, land loss, hunger, and deprivation fueled unrest among the Dakota. Three treaties signed over the previous 11 years reduced their land base, which severely restricted their access to food and other resources.

When treaty payments failed to arrive in 1862, hungry Dakota appealed to traders to sell them food on credit. Andrew Myrick, a representative of the traders, replied, “So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry, let them eat grass or their own dung.” The Dakota, betrayed and desperate, reacted to save their loved ones.

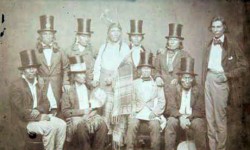

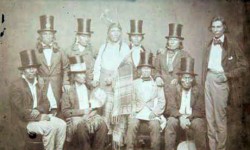

In 1858, this delegation of Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota signed a treaty that allotted their tribal lands on the Minnesota River. In the preceding 21 years, the Dakota relinquished nearly 24 million acres of land through treaties with the United States. | Photo by Charles DeForest Fredericks, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Little Crow’s Dilemma

Dakota Chief Little Crow faced a tough decision. He knew his people were suffering, yet he also knew the Americans were numerous and powerful and that war could have dire consequences. Should he lead his warriors in a battle for survival? Or should he counsel peace and risk losing the support of his young warriors?

Little Crow, reluctant leader of the Dakota conflict, in a photo taken during negotiations for the 1858 treaty in Washington, D.C. | Photo by Julian Vannerson and Samuel Cohner, James E. McClees Studio, courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Uprising

On August 17, 1862, four young Dakota men, returning from a hunting expedition, killed five settlers near Acton. Angered by a string of broken treaty promises and the loss of their territories, Dakota warriors chose to defend their lifeways in battle. Led by Chief Little Crow, who had advocated peace, the Dakota attacked traders and homesteaders, killing some 500 people. U.S. military forces engaged the Dakota in response. Five weeks later, the conflict was over.

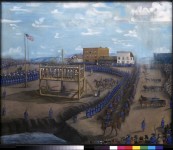

New Ulm massacre. From an oil painting by Anton Gag.

The Dakota faced revenge, punishment, and exile after the uprising of 1862. The United States nullified all of their treaties, sold their tribal lands, and redirected treaty payments to settlers who clamored for war reparations. Although most Dakota people were banished from the state, some returned to rebuild their communities in their traditional homelands.

Dakota tipis at a prison camp on the Minnesota River below Fort Snelling, 1862–63. | Photo by Benjamin Franklin Upton, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

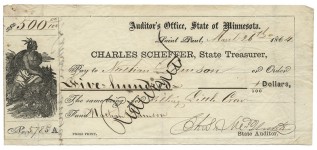

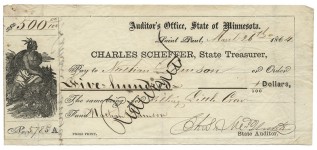

When the war of 1862 ended, Dakota women, children, and elders were rounded up and force-marched to a prison camp near Fort Snelling. Among them were Chief Little Crow’s wife and two children. Little Crow and other Dakota fled to Canada. While returning to Minnesota in 1863, the Dakota leader stopped in a field to pick berries, and was shot and killed by a farmer, who later collected a $500 bounty for “rendering great service to the state.”

“The President gave us some laws, and we have changed ourselves to white men, put on white man’s clothes and adopted the white man’s ways, and we supposed we would have a piece of ground somewhere where we could live; but no one can live here and live like a white man. “

— Dakota Chief Passing Hail, describing conditions at the Crow Creek Reservation, 1866

Little Crow’s wife and children | Photo by Benjamin Franklin Upton, courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Bounty receipt | Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Punishment

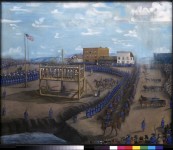

After the war of 1862, a military tribunal convicted 323 Dakota men of crimes committed during the conflict. During swift trials, 303 men were sentenced to death. President Abraham Lincoln stayed the execution of most of the condemned, but upheld the death sentences for 38 men. Those Dakota were hanged in Mankato on December 26, 1862, in the largest mass execution in American history.

J. Thullen, Execution of Dakota Indians, Mankato, Minnesota, 1884. | Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Exile

In 1863 Congress passed legislation that removed some 1,300 Dakota—nearly all who remained in Minnesota—on barges to Crow Creek in Dakota Territory, and then to the Santee Reservation in northeastern Nebraska.

Kevin Jensvold, chairman of the Upper Sioux Community, discusses the Dakota people’s deep connection to their homeland and their desire to return from exile.

Homelands

In the 1870s, exiled Dakotas such as the Santee Dakota of Prairie Island began to drift back to their traditional homelands in Minnesota. Traveling in small groups, they quietly re-established small communities near Morton, Granite Falls, Prior Lake, and Prairie Island. Today, there are four federally recognized Dakota communities in Minnesota, including the Upper Sioux Community, the Lower Sioux Indian Community, the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community, and the Prairie Island Indian Community.

Santee Dakota of Prairie Island | Photo by John Phillips, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

In 1867, the United States negotiated a new treaty that would relocate all Ojibwe in Minnesota to a new reservation: White Earth. Named for the layer of white clay that lies beneath the land, White Earth became home to many Ojibwe bands from central and northern Minnesota. But many Ojibwe resisted the removal effort, defending their treaty-guaranteed rights to retain their original reservation lands.

“My Friends, I want you to use your eyes and see who are suffering. … I came here [White Earth] to be better off. See who are the poor on this reservation. I will show to you those who have never received as much of what the Great Father sent as one could put on the end of a finger.“

— Sha-bosh-kong (Mille Lacs), speaking about conditions on the White Earth Reservation, 1877

Ojibwe men at the White Earth Reservation in 1872, four years after the community was created. Named for the layer of white clay that lies beneath the land, White Earth became home to many Ojibwe bands from central and northern Minnesota. | Photo by Hoard & Tenney, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Resisting Removal: The Mille Lacs Band

The United States exerted special pressure on the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe to leave their reservation and relocate to White Earth. When gifts of food, visits to the new reservation, and promises to finance relocation failed to induce tribal support for removal, federal authorities threatened to withhold treaty payments unless the band collected them at White Earth. Although some Mille Lacs leaders agreed to relocate most refused, insisting on the band’s treaty-guaranteed right to occupy their reservation.

Former residents of the Mille Lacs Reservation pose with their chief, Waweyeacumig, or Round Earth, (back row, fourth from right) at the White Earth Reservation in 1905. A long-time opponent of removal, the chief was finally persuaded to move to White Earth in 1903. The government agent who managed the band’s removal is seated in the front row, next to the little boy with the beaded sash and bag. | Photo by Robert G. Beaulieu, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Ojibwe, visiting Dakota, and non-Native people watch an American Indian dance performance at White Earth in 1910 during the annual June 14th celebration of the reservation’s creation under the treaty of 1867. | Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

In the 1880s, U.S. policy makers viewed reservation land, used in common by tribal members, as an obstacle to “civilizing” Indians. To hasten assimilation the government divided reservations into parcels for allotment to individual tribal members, with remaining land sold to non-Indians. By imposing the concept of private property on tribal communities, the government’s policy broke deep Native connections to the land and laid the foundation for the loss of tribal territories.

Basis of Civilization

“We have deliberated over the matter that you have laid before us. Your mission here is a failure.“

— Ne-quan-ah-quad, Red Lake tribal leader, speaking to U.S. government officials during discussions about the Nelson Act, which authorized the allotment of Minnesota’s Indian reservations, 1889

White Earth Ojibwe signing up for parcels of reservation land under the government’s allotment policy, 1890. | Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Losing Lands

Far from transforming Indians into self-sufficient farmers, allotment resulted in extensive tribal land loss and resource exploitation. As Indians lost title to their allotments through fraud and corruption, the ownership of reservation lands passed to non-Natives. By the 1930s, Indians owned less than ten percent of the White Earth Reservation, four percent of the Leech Lake Reservation, and seven percent of the Mille Lacs Reservation.

List of individuals who accepted land allotments on the White Earth Reservation, 1913. | Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Resisting Allotment: The Red Lake Band

Only the Red Lake Band successfully resisted the allotment of their tribally owned lands. U.S. government agents did their best to pressure Red Lake leaders into dividing up the reservation, but the chiefs held firm to a basic principle enshrined in their treaty: that Ojibwe had the right to hold their lands in common forever.

But at what price? Red Lake chiefs ceded 2.9 million acres in 1889 and another 256,152 acres in 1902—on top of the 11 million acres the tribe relinquished in the Old Crossing Treaty of 1863.

Delegation of Red Lake leaders to Washington, D.C., February, 1899. Photo by De Lancey Gill, courtesy National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

A crowd, including many non-Indian residents, gathers at White Earth to receive allotments of tribal land, 1905. | Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Dam-building projects on the headwaters of the Mississippi River threatened tribal lands and lifeways and ignited protests. The dams were intended to provide a consistent flow of water to float logs downstream and to power Minneapolis’s growing milling industry. Yet the dams also raised water levels, engulfing fish spawning grounds, wild rice beds, and Ojibwe grave sites.

“We now have only the pine lands of our reservation for our future subsistence and support, but the manner in which we are being defrauded out of these has alarmed us.“

Petition from the chiefs and headmen of the Pillager Band of Chippewa Indians, Leech Lake, Minnesota, 1898

Accessing Tribal Timber

Even after allotment, vast stands of timber were held by Ojibwe people, beyond the reach of lumber companies. In the early 1900s, Congress removed restrictions that prevented individual Indians from selling their allotments of tribal land, thereby opening the door to the exploitation of Indian timber reserves.

Minnesota lumberjacks standing near a load of numbered logs, 1910. | Photo by Harry F. Nixon, courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

The Winnibigoshish Dam

One of six federal dam projects built on Ojibwe lands on the Mississippi headwaters, the Winnibigoshish Reservoir Dam sparked a conflict between the Leech Lake Band and the U.S. government over compensation for damages resulting from the destruction of tribal property. After demanding fair compensation for almost a century, the band was awarded $3.3 million in 1985.

Winnibigoshish Dam under construction | Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division