As the United States expanded westward, treaties became the primary vehicle for acquiring Indian lands. Between 1837 and 1867, Dakota and Ojibwe bands in Minnesota negotiated approximately 16 treaties specifically ceding vast tribal territories to the United States. In exchange, the tribes were promised goods, services, cash payments, and reservations. At times, tribes retained access to resources on lands that were sold.

“I understand what you want . . . from the few words I have heard you speak. You want land.“

— Flat Mouth, chief of the Pillager Band of Chippewa, during treaty negotiations with U.S. officials, 1855

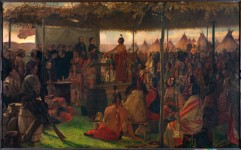

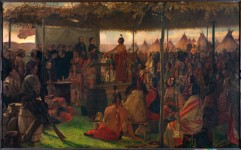

Francis Davis Millet, The Signing of the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux (detail), 1905. | Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Who Gave What to Whom?

Many people think that the United States gave land to the Indians, but the reverse is true. During conferences with U.S. treaty officials, Dakota and Ojibwe leaders agreed, often under pressure, to give up large portions of their homelands and retain small areas of land, called reservations, for the exclusive use of their people and descendants. In exchange, the United States promised to provide tribal nations with social, economic, and educational services, a responsibility that continues today.

![Notes from a meeting between the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs and leaders of the Mississippi, Pillager, and Lake Winnibigoshish bands of Ojibwe. The negotiations resulted in the Treaty of 1855, in which the Ojibwe relinquished vast territories in exchange for reservations and annual payments. [LINK TO: http://treatiesmatter.org/treaties/land/1855-ojibwe] | Courtesy University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center](http://treatiesmatter.org/exhibit/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/6.1-RESUP-1855-treaty-FINAL.jpg)

Notes from a meeting between the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs and leaders of the Mississippi, Pillager, and Lake Winnibigoshish bands of Ojibwe. The negotiations resulted in the Treaty of 1855, in which the Ojibwe relinquished vast territories in exchange for reservations and annual payments. | Courtesy University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center

Why Did Tribal Leaders Sign Treaties?

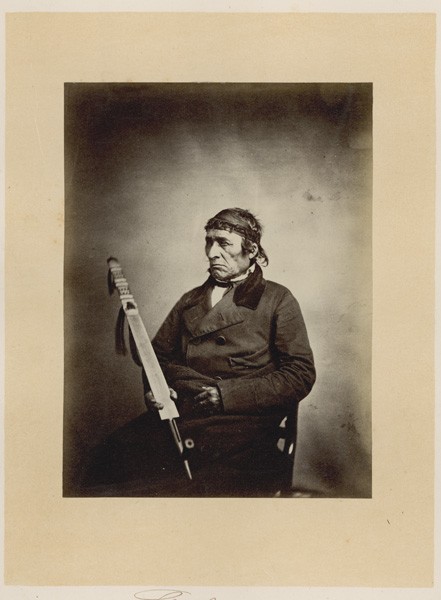

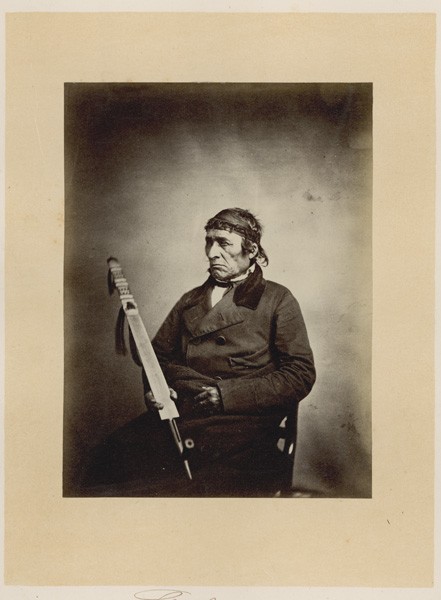

Shakopee was a member of a Mdewakanton Dakota delegation that negotiated one of two Dakota treaties in 1858. Signing treaties was sometimes the only way for Native leaders to keep their people alive. By 1837, the fur trade had declined and tribes were struggling to keep their economies afloat. As a last resort, tribes sold land through treaties in order to supply their people with money and food.

Shakopee, 1862 | Photo by Julian Vannerson and Samuel Cohner, James E. McClees Studio, courtesy National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Government to Government

As the leaders of nations, tribal chiefs often travelled to Washington, D.C., to negotiate treaties with U.S. officials. President Andrew Johnson and Native delegates, including Ojibwe Chief Bagone-giizhig, or Hole-in-the-Day, are pictured outside the White House in 1867.

Indian delegates at U.S. Capitol, 1866 | Courtesy National Museum of the American Indian P10142

Treaty Timeline

The Dakota and Ojibwe relinquished millions of acres through treaties with the United States. This map shows the dates of the principal land cession treaties, the extent of the land loss, and the location of present-day Ojibwe and Dakota communities.

Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Treaty Timeline

Land Cession Treaties

Tribal territories ceded through treaties were quickly put up for sale, fueling a huge influx of non-Natives to Minnesota. Speculators and surveyors measured and redistributed land for sale. Farmers, many of them poor European immigrants, built homes and planted crops. Lumbermen clearcut timber, which drove away game and eroded Native supplies of seasonal foods. This lack of reverence for the earth destroyed traditional Dakota and Ojibwe livelihoods and created widespread hardship.

“The greatest object of their lives seems to be to acquire possessions—to be rich. They desire to possess the whole world.“

— Dakota doctor and writer Ohiyesa (Charles Alexander Eastman), recalling his uncle’s description of American values in the 1860s

Julius R. Sloan, St. Anthony Falls, 1852. | Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Transition to Reservation Life

Government officials are pictured distributing treaty payments at the Fond du Lac Reservation around 1865. Relegated to reservations through treaties with the United States, Native people faced diminished homelands and food resources, and became increasingly dependent on government payments and provisions.

Reservation life also undermined traditional Indian culture and sovereignty. Accustomed to governing their own people, tribal chiefs were brushed aside by the U.S. government officials, or “Indian agents,” who were sent to manage reservations. Corruption ran deep among Indian agents, who often lined their pockets with treaty payments and provisions.

Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

A Clash of Cultures

American notions of property confounded Ojibwe and Dakota peoples. Land was a gift from the Creator. How could something sacred—something that was meant to be shared in common—be traded for money?

“To Promote Their Improvement and Civilization”

Treaties of the 1850s and ’60s sought to eliminate tribal cultures by encouraging Indian men to spurn hunting and adopt farming. Schools were established to instruct Native children in the knowledge and values of American society, and Christian missionaries extolled the virtues of conversion. To cultivate individualism, some treaties divided collectively owned tribal lands into parcels for distribution to individuals, foreshadowing U.S. allotment policy of the 1880s.

Ojibwe girls in a classroom at the St. Benedict’s mission school, White Earth Reservation, ca. 1900. |

Ojibwe bands continue to hunt, fish, and gather wild rice as they have for centuries. These rights are recognized in the land cession treaties of 1837 and 1854. By signing these treaties, tribal leaders ensured that future generations would be able to access natural resources on former tribal lands.

“The privilege of hunting, fishing, and gathering the wild rice, upon the lands, the rivers and the lakes included in the territory ceded, is guarantied [sic] to the Indians, during the pleasure of the President of the United States. “

— Article 5, Treaty with the Chippewa, 1837

Two men holding rifles near Mille Lacs, 1899. | Photo by David Bushnell, courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Ricing

Known as manoomin in the Ojibwe language, wild rice has been a valuable Native American food source for centuries. From before the treaty-making era to today, Ojibwe families have harvested wild rice each fall on their ancestral lands.

Ojibwe woman with container of wild rice, 1940. | Photo by Gordon R. Sommers, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Sugaring

In the spring, people set out from their villages to collect maple sap, which women boil down into sugar.

Two Ojibwe women cooking maple sap at a sugar camp, possibly at the Mille Lacs Reservation, 1915. | Photo by Frances Densmore, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Gathering

Treaties guaranteed Ojibwe rights to gather food and medicinal plants on former tribal lands. In the summer, families set up camps to gather blueberries, which grow in abundance.

Ojibwe woman gathering blueberries near Little Fork, Minnesota, 1937.| Photo by Russell Lee, courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Hunting

Even after they accepted reservations, Ojibwe people exercised their right to hunt game on lands relinquished to the United States.

Anton Treuer of Bemidji State University discusses the Ojibwes’ retained right to hunt and fish on ceded lands.

Fishing

As retained by treaties, Ojibwe continue to harvest fish both on and off reservations. More than 150 fish species are found in Minnesota’s inland lakes and streams as well as in Lake Superior, including bullhead, perch, pickerel, walleye, and whitefish.

Mary Razer (Mille Lacs Ojibwe) draws her gill nets from a lake at the White Earth Reservation around 1915. | Photo by Frances Densmore, courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

![Notes from a meeting between the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs and leaders of the Mississippi, Pillager, and Lake Winnibigoshish bands of Ojibwe. The negotiations resulted in the Treaty of 1855, in which the Ojibwe relinquished vast territories in exchange for reservations and annual payments. [LINK TO: http://treatiesmatter.org/treaties/land/1855-ojibwe] | Courtesy University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center](http://treatiesmatter.org/exhibit/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/6.1-RESUP-1855-treaty-FINAL.jpg)